Leiden's crowded, cosmopolitan city life contrasted with the largely self-sufficient, seasonal, crop-oriented farming background of many of the Pilgrims. For Pilgrims from London, Norwich and other cities, used to urban markets, the changes were less radical.

Most Leiden houses were small; a single room with floor space of about nine by twenty feet was not unusual. A three-foot wide entryway beside the room led to a stairwell to a loft, and under the stairs was a bedstead opening into the room opposite the fireplace. Even with the loft above under the rooftiles, where some of the older children could sleep along with the barrels of flour and other supplies, family life was less than spacious.

Slightly larger was the typical weaver's house, where an unheated front room gave space for a large loom, lit by a tall window on the street. A cross-wise stairway divided this room from the rear, and under the stair was a built-in bedstead facing the rear room, where the fireplace could be used for heat and cooking. Upstairs under the eaves there was generally a small finished room in front, with a low ceiling providing a little attic storage above, and a storage loft in the rear.

Often there was a little place out back for a goat and some chickens. Such houses were smaller than what could be built in the future colony of Plymouth Plantation, where land was unrestricted.

Although there were shops for a variety of craft products, and some products such as cloth were sold twice weekly at the guild hall, food was bought in the open-air markets. Leiden's weekly markets were arranged along the Nieuwe Rijn, as they still are today. Produce brought to market was unloaded at the City Crane, on a little quay extending into the water in front of the Weigh House.

Today's markets take up less space than they did in the seventeenth century, as we are reminded by street names along the water where there are no longer any markets, such as the Tree Market (Boommarkt), the Animal Market (Beestenmarkt), and Eel Market (Aalmarkt). The meat market has also disappeared. This was formerly on the Breestraat, in part of the Town Hall. Across the street, extending from the Breestraat to the Lange Brug (where Pilgrim James Chilton and his family lived) was the Tripe Market, for cheaper cuts of meat and for poultry. Its ornamental gateways are still to be seen, one of them just around the corner from the Brewsters, living in the Pieterskerk Koorsteeg. Those Pilgrims who lived in the Green Close behind John Robinson's house at the other end of the Pieterskerk could grow vegetables in the small amount of ground in the center of their quadrangle; others lived in houses with no garden space.

Labor was expected from dawn to dark, six days a week. A bell in a tower on the Yarn Market (Garenmarkt) was rung to let people know when work was to start and end. As soon as they were old enough to help out, children participated in the tasks of their fathers and mothers. Children sometimes learned to read and write in the evening, after work, although Pilgrims complained later that in Leiden they had been unable to provide their children with adequate educations. Light at night came from candles and from less expensive oil lamps, which burned fish oil as well as vegetable oil from pressed seeds, ground by windmill or horse-drawn mill. Rush-lights were made from reed pith soaked in fat drippings.

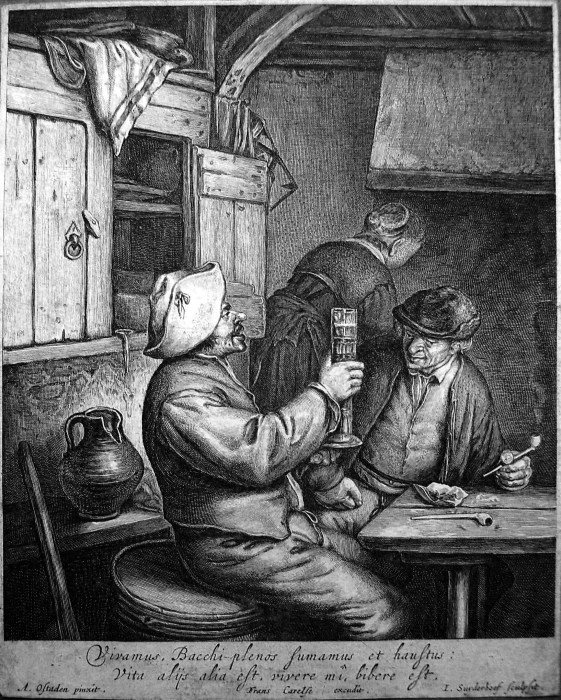

The water in the canals was not fit to drink. Many houses had cisterns under the floor, for holding rainwater run off through drain pipes from the roof. These cisterns were sometimes side by side with the pits of indoor privies or outhouses. Beer was considered a healthier drink than water. Beer for home use had to be fetched in jugs or small casks from nearby inns or taverns. (An advantage of being registered as a member of the university was an annual allowance of tax-free beer; Robinson may have shared this bounty.) There were many more taverns and inns than there are now, and these formed a social focus for many people escaping crowded houses in the evenings. Some bore names that indicate they probably appealed to specific groups of foreigners, such as the inn called "In the Sign of Sandwich" near the house of Pilgrim Richard Masterson, which must have been one of the places to find English expatriates. Taverns were also where tobacco was sold and "drunk" by people sitting around a table where an earthenware pot holding coals was used to light the small clay pipes.

Inns were also places where business deals were made and oral contracts were closed. The contracting parties treated everyone else to a round of drinks. The inn-keeper served as a witness to the contracts in his inn, if called on to do so in court later. More formal contracts and wills were drawn up before a notary.

Neighborhood matters such as fire protection (householders had to provide buckets and ladders), street repair, the night watch, burial of the dead, and some aspects of poor care, were the responsibility of neighborhood officers elected annually by each of the 77 little neighborhoods in a local inn considered the neighborhood house. As was the case with other officers, such as deacons of the Reformed churches, the election was subject to confirmation by the burgomasters.

The routine of daily life was sometimes interrupted. Five major fairs occurred throughout the year, three for leather and hides, one for cheese, and a general fair lasting ten days commemorating the lifting of the Siege of Leiden in 1574. Leiden was also visited by travelling musicians and actors, including a troupe of English comedians in 1610. The most important special festive event in the Pilgrims' Leiden period was the visit of the Queen of Bohemia (Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James I of England) in 1613.

Fifteen different inns were needed to house the accompanying dignitaries and their servants.

The Pilgrim’s rich and exciting story deserves to be told in detail. You can discover different aspects of it in the following chapters.