Our collections are diverse and rich. Furnishings from Pilgrim times show aspects of daily life, while events involving the Pilgrims themselves are illustrated with a remarkable collection of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century maps and engravings by such artists as Gerard Mercator, Adrian van de Venne, Adriaen van Ostade, and Jacques de Gheyn. You will find here a few gems we conserve illustrating the variety of our collections.

A Fire-cover or curfew

Tin-glazed earthenware, 1655-1665, Netherlandish, probably from Friesland

Tin-glazed earthenware, 1655-1665, Netherlandish, probably from Friesland This green-glazed ceramic is shaped like a half-bell with a handle on the top. Placed on the hearth and against the wall, it would keep the embers burning safely until it was revived in the morning.

The holes on top allow for the smoke to go up, while the pottery protects the low fire from the wind coming from the chimney.

The English word “curfew” derives from the French “couvre-feu” (fire cover); when this object was placed in the fireplace, the day was late and it was time for children to be inside, which led to the modern meaning of the world curfew, typically an order to stay indoors after a certain hour.

This object could be called avondklok in Dutch, which is also the modern word for such an order.

Our curfew is decorated with various figures moulded separately from the body and applied afterwards, before the whole piece was glazed evenly and fired. We can see some portraits as well as mystical creatures: a griffin, a merman and a unicorn.

Some faces have names: Philip IV of Spain (1605-1665), Pope Alexander VII (1599-1667) and Louis XIV of France (1638-1715). Assuming the craftsman or the buyer cared about being up-to-date, this dates our fire-cover between 1655 (when Alexander VII became Pope) and 1665 (when the first of the three passed away).

This also suggests that the owner was Catholic. One portrait is missing on the right of the object, with a name starting with “W”.

We could venture to guess that it was a representation of Willebrodus, shown as the founder of Catholicism in the Netherlands and important saint in Friesland, where this pottery was crafted.

Fire prevention was a very important aspect of housing safety in a dense city where most buildings have timber frames and various amounts of wood panelling: the start of a fire could mean the destruction of a whole neighbourhood in a matter of hours.

Inhabitants were required to own fire buckets in case of emergency, to help extinguish the flames.

As it was compulsory in a 17th-century home, our museum holds one of these leather buckets too, a very rare artefact as many of them only remain in fragments while ours is complete!

It bared a house mark (illegible today) to make it easier to give back to the right family after putting out a fire, and a date which appears to be 1608.

A Westerwald jug

Stoneware, c.1600, Germany

This jug now sits on our table. Grey and blue stoneware pottery from Germany - Westerwald ware - was shipped down the Rijn (Rhine) River and sold in large quantities in The Netherlands. Some pieces were made specially for the Dutch market, including, for example, pieces presenting the coat-of-arms of Amsterdam.

The Leiden American Pilgrim Museum has exhibited examples of such Westerwald pottery since the museum's opening. Fragments of Westerwald pottery have been found in Plymouth excavations (the Eel River site, known as RM), as well as in Martin's Hundred in Virginia and in the Dutch colony of New Netherland. This particular jug incorporates design elements like those in the Plymouth fragments, it is also very similar to the Virginia example, which is illustrated in Ivor Noel Hume's Martin's Hundred (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982, ill. 7-4), and a couple of years ago, fragments including a rosette like what is on the shoulder of ours were found on Cape Cod.

We can picture settlers packing some of these elaborate potteries for their journey to America. There was not much space on the ships crossing the Atlantic, therefore people had to select wisely what to bring: essential, useful items for daily life and survival, and precious artefacts that they could not easily obtain or make once they arrived. Our ceramic falls in the latter category. It sits on our table next to a wooden plate, a coopered beer mug, and a knife, all ca. 1600, in a presentation that is identic to a layout of the time.

Seutter’s Map of Novi Belgii

Engraving with watercolours, 1740

This map was engraved and first published in 1730, but its information for New England is derived from the famous Jansson-Visscher maps of New England first issued in 1651. Mattaeus Seutter's version is the first to show the boundaries of Massachusetts, New England, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania; but examination shows that the geographic information of interior locations is about a hundred years out-of-date, while the information for Plymouth Colony is about right for what was known in Europe ca. 1630. A major feature of importance is the visual depiction of animals and of Native American houses, which, together with the names of Indian tribes, makes it possible to imagine the earliest settlers' conception of the vast land and its inhabitants when they first began their villages along the coast. One can read “Patuxet at Neu Pleymont” on the spot where the Pilgrims first settled, giving us the Indigenous as well as the colonists’ name for the place. The map indicates names in German and in Latin, hence some repetition, like “Neu Niederland” and “Nova Belgica” (which does not refer to modern-day Belgium of course, but to the Roman name for the Low Countries). Matthaeus Seutter was born in Augsburg in 1678. He was appointed Imperial Geographer in 1731 by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI. He died in 1757. Our acquisition of this important map was made possible by a very generous gift.

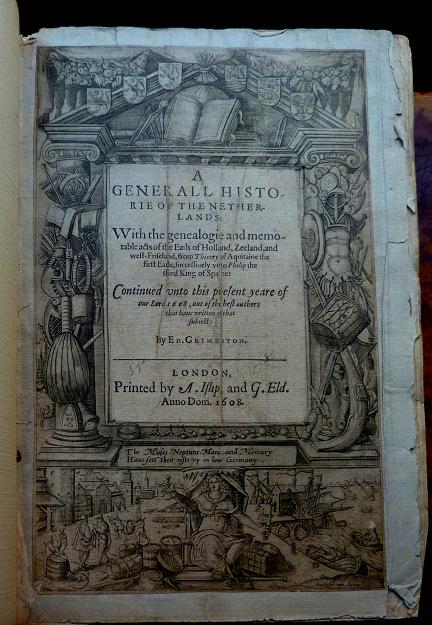

Edward Grimstone

A Generall Historie of the Netherlands

Book (paper and leather cover), London, 1608

Not all pilgrims knew how to read, but some of them owned extensive libraries and travelled with them to America. The books included various topics, from theology to botany, military strategy, and like this volume illustrates, history. Edward Grimstone's English translation of Petit's A Generall Historie of The Netherlands was published in London in 1608.

William Bradford mentions this book (even citing the particular page number) in Of Plimoth Plantation as the source for information about the Dutch law establishing civil marriage, which the Pilgrims adopted in the laws of Plymouth Colony. It did not exist in English law at the time. This was the first step towards legal separation of church and state. The book also provides translations of the Union of Utrecht (1579), a model for the Act of Confederation of New England Colonies, and of the Act of Abjuration (1581), which strongly parallels the Declaration of Independence (1776).

Several pages also show beautifully detailed engravings of political figures by Christoffel van Sichem, among which Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester, whom Brewster had known personally. How interesting to think that Dutch artworks of such quality made their way to America with the Pilgrims.

Light reflector

Late 1585- early 1586, copper (The Hague?)

On our table lies a brass light reflector – not to be confused with a plate! The shiny, reflecting properties of copper were ideal to make these items. Cleverly placed around the room, close to a candle, the round objects would reflect the light of the flame. At the time, houses after sunset got very dark and candles were an expense: any trick to increase the lighting of a room would be welcome.

Our reflector has a unique story. It was created for a special occasion, namely the 1586 welcoming in The Hague of Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester and named governor-general of the United Provinces by Queen Elizabeth I. A night parade was organised for the occasion: part of it was a chariot carrying dozens of these reflectors with a candle in front of each one. An engraving by Jacob Savery (I) immortalizes the scene. What a beautiful and striking sight it must have been in the streets at night. Diplomats and their assistants and servants made up the parade, together with the militia guilds and perhaps other guilds. Future pilgrim William Brewster was part of Dudley’s retinue: he surely witnessed this spectacle and took part in it. Our object is repoussé and engraved to obtain a concentric decor of Tudor roses, French fleur-de-lys and garland. It is always exciting to be able to present to our visitors artefacts which actually crossed the path of pilgrims.

Great Screw

Wood and iron, 17th century

William Bradford recalled the furious Atlantic storm that broke the main beam of the "Mayflower" in her voyage to New England in 1620. Fearing leaks, Master Christopher Jones and his crew inspected the hull by candlelight, rib by rib and plank by plank. Reassuring the Pilgrims, they "affirmed they knew the ship to be strong & firm under water; and for the buckling of the main beam, there was a great iron screw the passengers brought out of Holland, which would raise the beam into his place; the which being done, the carpenter & master affirmed that with a post put under it, set firm in the lower deck, & otherwise bound, he would make it sufficient. And as for the decks & upper works they would caulk them as well as they could, and though with the working of the ship they would not longe keep stanch, yet there would otherwise be not great danger, if they did not overpress her with sails. So they committed themselves to the will of God, & resolved to proceed" (extract of Of Plimoth Plantation).

The Great Iron Screw inspired a myth that has entered Pilgrim historiography with almost unconquerable persistence. J. Rendel Harris asked in 1922, "what the emigrants were doing with a great iron screw. It would have been one of the last things a company of exiles would have laden themselves with." But he turns the question around, to ask why the Pilgrims had owned such a screw in Holland, since they "were not likely to have secured it as a new acquisition when they were departing." For Harris, "The answer is obvious; it was part of the printing press, which the Leyden authorities had not carried off. There was no object in leaving it in Leyden; the two printers on board the ship (Brewster and Winslow) might have been reluctant to part with it. Perhaps they even thought that in a few years' time they would be able to import some type, and begin once more their civil and spiritual propaganda. It is certainly curious, this story of the great screw, and, up to the present, has never been elucidated." [...] The idea that the Pilgrims took a printing press to America in 1620 was thus born in Harris's imaginings inspired by the anniversary year 1920 and first published in 1922. [...] Quite a different answer can be given to Harris's rhetorical question (what were the emigrants doing with a great iron screw). Joseph Moxon, in his book Mechanick Exercises (first published 1678-1680) describes all the tools used in "house-carpentry." He remarks, "There are also some Engines used in Carpentry, for the management of their heavy Timber, and hard Labour, viz, the Jack, the Crab, to which belongs Pullies and Tackle, &c. Wedges, Rowlers, great Screws, &c." The term "great screw" thus referred to a particular tool. Needed in the construction of a home, a Great Screw could raise the roof, as Moxon informs us. [excerpted from Bangs, Strangers and Pilgrims, Travellers and Sojourners pp. 607-609]"

Pilgrim William Jepson was a housewright and carpenter -he may have owned such a tool while he worked in Leiden. Moreover, everyone who grew up on a farm, like most people in the congregation did, had experience building and repairing barns and shed. The Pilgrims were thus familiar with such tools and techniques. Travelling with house-building tools to America was indispensable for a long-term settlement and must have come as evident for the group.

Catholic banner

Dyed linen and paint, end of the 15th century

The museum has pre-Reformation collections displayed in our medieval room, of which the interior dates back to 1365-1370. This banner is one of our most exceptional pieces of that early period. Made at the end of the 15th century, it was dyed blue and the figures and symbols were painted with an egg-based paint. Their style indicates a provenance from the area of Haarlem.

This flag was a devotional aid in a chapel inside a church - almost certainly a chapel of a devotional guild of the Holy Cross (as indicated by the side of the banner that has only the cross on it). The habit was to recite rosary prayers with topical emphasis on each of the moments in the story, inspired by the symbols referring to the moment. It could also be used for the celebration of Easter, during which a procession in the streets was organised, when the cathedral took out artworks to present to the population.

The iconography on this banner is similar to the arma Christi, or the instruments of suffering. Each symbol represents one moment in the story of the Passion, and believers were supposed to reflect and repent on each of them.

This specific representation here is a forerunner of the Stations of the Cross, by which the devout could contemplate the whole story from Gethsemane to the Resurrection by meditating on the several symbols in the correct chronological order. More than a liturgical tool, this banner is a visual summary of the story, a narration that would have been understood by all the population, far more than prayer and recitations in Latin, or biblical texts that many people could not read.

One image encompasses all events of the Passion, and while Christ may not be visible on the Cross, his presence is made clear by the blood he shed around the nails. The basin refers to Pilate washing his hand after the trial, the hammer to planting the nails in the Cross, the dice to the Roman soldiers gambling over the robe of Christ, etc. These symbols were all recognisable to a contemporary viewer. The figure of Mary in lamentation at the foot of the Cross reveals by her delicate features the talent of the painter.

This painting was acquired in Haarlem. Its similarities to other paintings suggest it was probably made by someone of the Van Waterland family, whose several members who were painters received numerous commissions for work in the St. Bavo Kerk (Grote Kerk). This banner is not documented. Religious artefacts before the Iconoclasm (1566) in the Netherlands are rare.

This banner is the only one known in the country today.

For more about the Van Waterland family, see Jeremy Dupertuis Bangs, The Masters of Alkmaar and Hand X : the Haarlem painters of the Van Waterlant family, Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch / hrsg. im Auftr. der Freunde des Wallraf-Richartz-Museums und des Museums Ludwig e.V., Köln. 60. 1999, pp.65-162