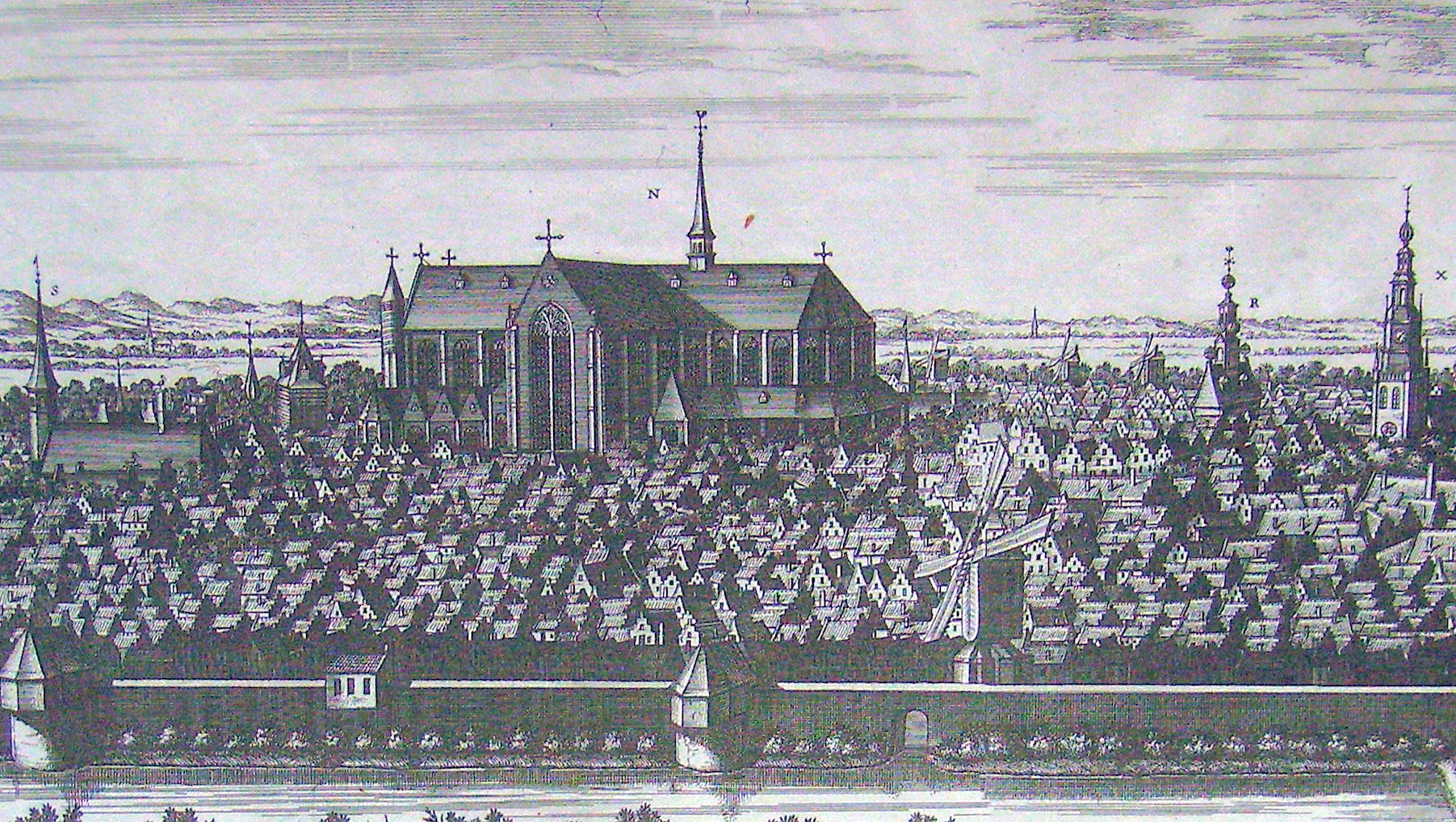

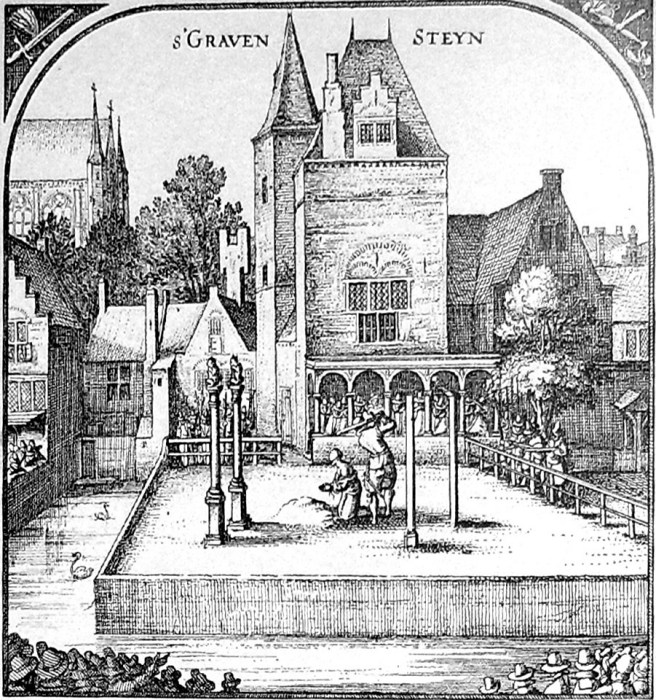

Leiden, where the Pilgrims sought refuge in the spring of 1609, was a town of refugees. Lying on a Roman road, now called the Breestraat, Leiden had been a city since around the year 1200, when its castle the Graven Steen was the residence of the Count of Holland. Another older castle, the round Burcht, dominated a place where a major north-south road crossed the Rijn River and the Roman road, and where the river itself forks into three main streams. The Vliet flows south, passing The Hague and Delft then, as the Schie, to Schiedam and Delfshaven; the Rijn runs west into the ocean at Katwijk; the stream of the Mare and Leede flows northwards to the Haarlemmermeer (now drained), a lake connecting with Haarlem and Amsterdam.

Taxation crippled Leiden's medieval cloth industry to pay for the wars of Charles V and Philip II in the sixteenth century. While the king attempted to crush the Reformation, Leiden, in 1572, joined the Reformed movement and chose for the side of William the Silent, Prince of Orange. He led the revolt against Spanish domination that eventually brought independence to The Netherlands. In the years 1573 and 1574, however, Leiden endured a long siege by the armies of Philip II. More than 6,000 of Leiden's citizens, slightly more than half the population, died of starvation and epidemics. The Dutch navy broke the dikes and sailed in flatboats right up to the city walls to free the town. Because Leiden had been able to withstand a military siege, it was considered a suitable location for a university, founded in 1575. It was also granted new trade fairs, one of which lives on in the annual October Third celebration that grew up around the special Thanksgiving service in the Pieterskerk proclaimed the day the town was liberated in 1574.

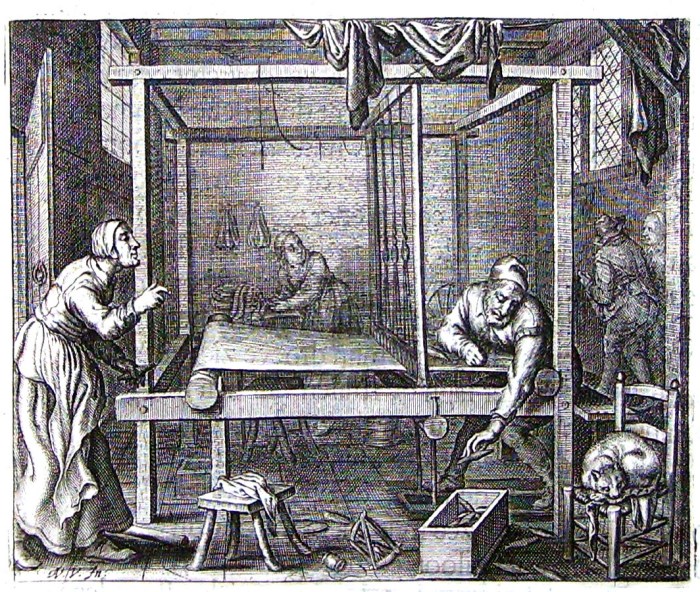

An influx of refugees brought the number of residents to around 12,000 by 1580, and around 40,000 by 1620. Leiden's city walls had to expand in 1611, when no more houses could be built in the gardens of the older residences. A city extension was carried out all along the northern side of the town. About a third of Leiden's inhabitants were refugees from Belgium, and among so many thousands of newcomers, the group of 100 Pilgrims arriving in 1609 attracted little attention, although the city specificaly granted them permission to come live in Leiden and further protected them by refusing to repudiate them when asked by the English ambassador. The city welcomed refugees to work at the looms. With countless families carding, spinning, and weaving from dawn to dusk, the drapery industry revived. In 1612 alone, more the 95,000 large pieces of cloth were produced which were inspected and marked with Leiden's official lead seals of quality. About half the Pilgrims became textile workers while living in Leiden. Cloth was not Leiden's only major industry, of course, and throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, for example, Leiden brewed two and a half times the amount of beer that was consumed within the city boundaries.

During the middle ages, and again since the recovery following the siege of 1574, Leiden obtained its wealth through international trade. It produced and exported cloth, cheese, parchment, pewter, oils, books, beer, and bricks to places as far away as Russia, England, and Spain; and it imported grain and wood from Poland and Scandinavia, wool from England and Spain, and spices and alum from Italy. New civic buildings arose to reflect the new wealth; the City hall, designed in 1595; Rijnlandshuis, from 1599, seat of the territorial government of Rijnland; the ancient Latin School, given a new facade in 1599; and the city Timber Wharf from 1612; besides new city gates, all but two of which have since been demolished. The timber wharf was the depot for all the oak beams that had to be imported from the Baltic for the new houses being constructed to house Leiden's growing population. Leiden was a fountain of academic publishing; and it was again becoming a major artistic center as it had been in the earlier 16th century. When the Pilgrims were in Leiden, the Latin School counted among its pupils Rembrandt van Rijn.

The Pilgrim’s rich and exciting story deserves to be told in detail. You can discover different aspects of it in the following chapters.