The museum is constantly looking to enrich its collections with pertinent and significant items from the periods we deal with. Here are our latest additions.

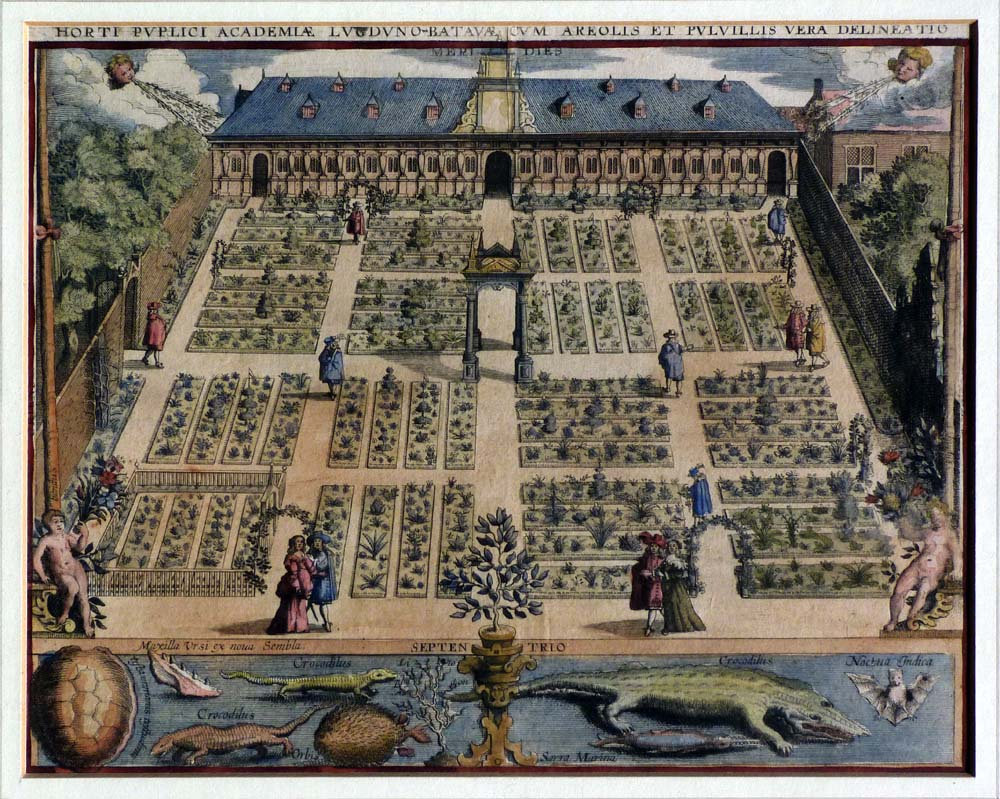

An engraving of the Hortus Botanicus

Engraving and watercolour, Willem Isaacsz. van Swanenburg (1580-1612) after Jan Cornelisz. van 't Woudt, 1610. The inscription “J[ohannes] Tangena excud[it]” has been clumsily added to the original plaque, in the middle of the French poem underneath the scene. Johannes Tangena was a map and print seller who had a shop near the Leiden city hall in the later 17th century (ca 1690). No other changes were added to the original copper design

The museum has just acquired two 17th century engravings! This print is part of a series of four engravings related to Leiden University from 1610. The others represented the library, the fencing school (both in the same building at the time) and the anatomical theater. This one is a depiction of the botanical garden, the first one in the Netherlands (1590), started by renowned botanist Carolus Clusius. The scenes highlighted the academic excellence of the University. On the canal Rapenburg, next to the Academy building, the Hortus Botanicus was a place of study that welcomed university students as well as the general public. On our engraving, we can see the neatly organized square garden with small paths along which people are strolling. Some of them seem to be taking notes. At the bottom corners, putti are bearing flowers. As seen on many still-life paintings, flowers were very appreciated by the Dutch. The most sought-after and expensive at the time were tulips. The tulip industry started here, in the Leiden garden, with the works of Clusius importing them from Turkey, growing them and studying them.

At the bottom of the print, some items of natural history preserved at the time at the University are visible: a turtle shell, a bear’s jaw, crocodiles, a puffer fish, coral, a saw shark and finally a bat. The latter is also represented in a woodcut in Sebastian Münster’s description of the world, De Cosmographia.

Botany was a science of great importance for the Pilgrims on their journey to America. They took a Herbal with them, written by Leiden University’s professor Rembout Dodoens, to help with medicine and food. Pilgrim Samuel Fuller, who became Plymouth colony’s surgeon, could educated himself in medicine thanks to the public access to the anatomical theater and the hortus botanicus in Leiden.

An engraving of the Arminian barricade in Leiden in 1617

Engraving, 1618

This historical engraving is a view of the Breestraat of Leiden in 1617, when a portion of the street was closed off by barricades. On the left is the town hall (‘t Ratdhuys) with its spire and its double staircase on the Renaissance façade. On the horizon line, we can see the Hooglandsekerk, the Looihal and the Baginhof. Within the central perspective of the wide street with its stepped gables, soldiers are going about standing in neat formation, attending the cannons, guarding the street and fighting off attackers. This artwork is a much more detailed version of a print the museum already owned. We can see more precisely how the situation unfolded in an area of the city that looks very much the same today. The unrest and the defensive settings organized as a result was caused by the theological opposition between the Remonstrants, followers or Arminius, and the Contra-Remonstrants, followers of Gomarus, two theology professors at Leiden University. Fearing violence, the Remonstrant magistrates ordered the barricades to be built across the main street at both ends of the city hall.

“The barricade, soon known as the Arminian Redoubt (Arminiaansche Schans), consisted of a sturdy palisade of heavy timbers and pickets, eventually fitted with spikes along the top, that were popularly dubbed “Oldenbarnevelt’s teeth.” Small doors with sentries, who could open the wider cart-gates when required, allowed people through to conduct business when official occasions were peacefully happy, the expectation of armed conflict was unavoidable. Three Pilgrim couples registered their betrothals and marriages in the city hall while the Arminian Redoubt was in place: Rose Singer and Steven Butterfield (betrothal just ten days after the riot, October 13, 1617); Janet Paul and Henry Jepson (December 8); Elizabeth Barker and Edward Winslow (April, 1618).” Jeremy Bangs, Strangers and Pilgrims, p.535

The Pilgrims were familiar with the theological questions at the heart of this incident and followed the debates with interest; Rev. John Robinson even gave a lecture in the theology room of the Academy Gebouw of the University defending Contra-remonstrant views. However, valuing debate and reflection, the English separatists were strongly opposed to the views of the Remonstrants without wishing for a violent resolution of the argument. The aggressive response of Prins Maurits following the Synod of Dort (1618), condemning the Arminians and subsequently executing some of them, was against the Pilgrims’ vision of religious freedom. To them, just as every man and woman is imperfect after the Fall, every human theology could be flawed, and for this reason a certain understanding and tolerance must exist.

A miniature “Carver chair”

Wood and caning, 17th – 18th century (?)

This miniature (30 cm high) piece of furniture is a model or doll chair. It is called a “Carver chair” as a reference to a historical artifact today preserved at Pilgrim Hall, MS. Made around 1630-1670 in America, its ownership was once attributed to John Carver, the first governor of Plymouth Colony.

However, Carver died in 1621, which makes it highly unlikely that the chair ever belonged to him.

Nevertheless, his name stayed attached to this type of chair: the piece is turned with armrests and three vertical spindles in the back.

Other designs of Early American furniture are named after pilgrims based on artefacts found in Plymouth colony, like the Brewster chair, presenting a more complex design than our Carver chair.

Tailor tile

Blue and white tin-glazed ceramic, c. 1650

This blue and white tile depicts a tailor at work.

The character is working on a piece of clothing with a thread and needle, while other tools are lying around him: a measuring stick, a bobbin, a pair of scissors.

We also have some of these tools in our collections!

Many Dutch tiles have designs representing occupations.

For the museum, it is a great way to illustrate various activities with objects from the time.

The character on this artefact is sitting down to work. Often, tailors sat on tables by a window to conduct their work with as much daylight as possible.

Seven pilgrims, among which Isaac Allerton, were tailors.

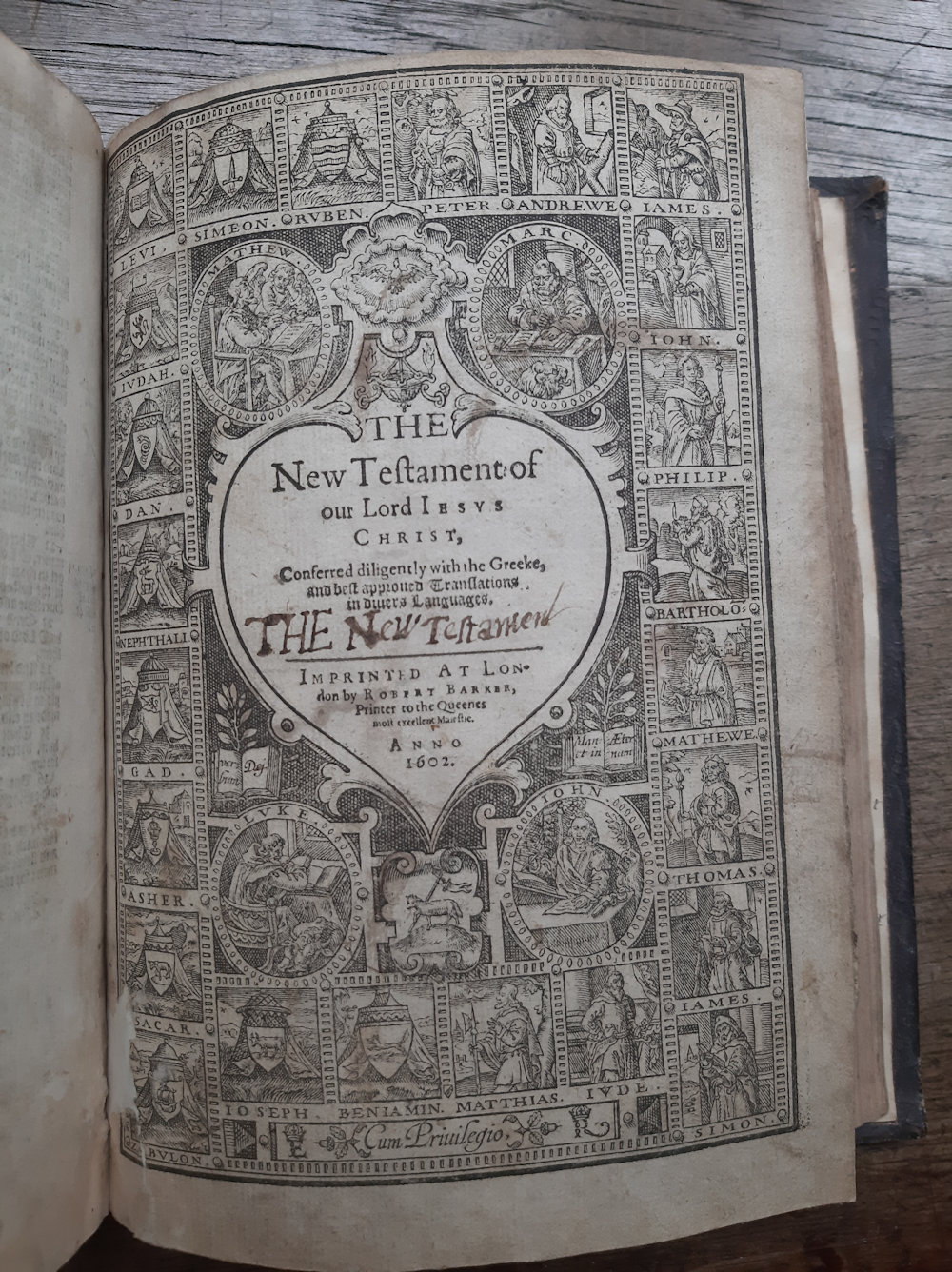

A Geneva Bible

London: Robert Barker,1602.

Book (paper and leather cover)

The Geneva translation of the Bible was translated by English Protestant exiles in Geneva during the reign of Queen Mary Tudor (first edition: 1560). The museum has now acquired a copy from the 1602 London edition which was rebound in the 19th century. The Geneva Bible is also known as the "Breeches Bible" because of its unusual translation in Genesis 3:7 - "Then the eyes of them both were opened, and they knewe that they were naked, and they sewed figtree leaues together, and made themselues breeches." The Geneva translation was preferred by the Pilgrims, especially in contrast to the King James Version, because of its marginal explanations.

On this engraved title page for the New Testament, we can see various characters, especially the four apostles, Matthew, Marc, John and Luke, the Agnus Dei and the Holy Spirit encircling the title. A clumsy (and probably 17th -century) hand seems to have practiced its letters by copying the title.

Buttons

Copper, 17th century

The museum holds treasures big and small. These cast copper buttons were probably ornamenting a man’s doublet (a fitting jacket), about 15 to 20 of them on the front. On the only known depiction of a first-generation pilgrim, the portrait of Edward Winslow (Pilgrim Hall, Plymouth, MS), we can see him wearing such a piece of clothing with ornate, shiny buttons. Our buttons gave probably a similar effect once polished. It is important to remember that someone posing for a portrait is likely to be wearing some of his or her nicest clothes. These paintings do not represent every day fashion for ordinary people. Clothing hooks sewn onto the underside of garments could replace buttons - contrary to our little metal ornaments here, they would be invisible.

Every one of them has a slightly different pattern: flowers, Solomon knots, waves and woven patterns. Some floral decorations are very similar to silver buttons excavated at Plymouth Plantation. From these small artefacts, we can tell than people paid attention to detail when they could afford it. Buttons could be made of cheaper materials, like wood.